Short answer

Our brain is always guessing what’s happening in the world around us. What we consciously experience, is a combination of these predictions and the sensory input that we receive (through our eyes and ears for example). When sensory input is unclear, such as in the “brainstorm / green needle” audio fragment, our conscious experience is mostly determined by our predictions (here: the instruction to hear “brainstorm” or “green needle”).

Longer answer

Full HD widescreen 3D experience

Consider the case of visual perception, or how we see the world through our eyes. Our detailed color vision is mostly limited to an area about the size of a thumb held at arm’s length. This is what our brain has to work with; a tiny snapshot of our visual environment. This snapshot is replaced by a completely new snapshot about three times per second, each time we make an eye-movement. This surprisingly limited sensory input stands in stark contrast with our conscious experience of the world, which is incredibly rich and full of colors and details, depth and motion, and spans from floor to ceiling and left to right. How does our brain create this rich experience of the world, from the minimal sensory input (the snapshots) that we receive moment by moment?

The brain as a prediction machine

The answer may be surprising: what we perceive (our conscious experience of the world) is not a copy of the outside world that we register through our sensors (our eyes and ears)! Instead, it is a “simulation” created by our brain. A simulation that represents the most likely state of the world, based on both our expectations (top-down signals) and our current sensory input (bottom-up signals). The stronger our expectations about the world, and the noisier (or more uncertain) our sensory input is, the more our conscious experience reflects what we expect rather than what we actually sense. Conversely, the weaker our expectations are, and the more clear and detailed our sensory input is, the more our conscious experience will reflect what we sense. More generally speaking, our conscious experience reflects the brain’s best guess about the state of the world: a delicate balance between what we expect and what we actually sense.

Multiple interpretations

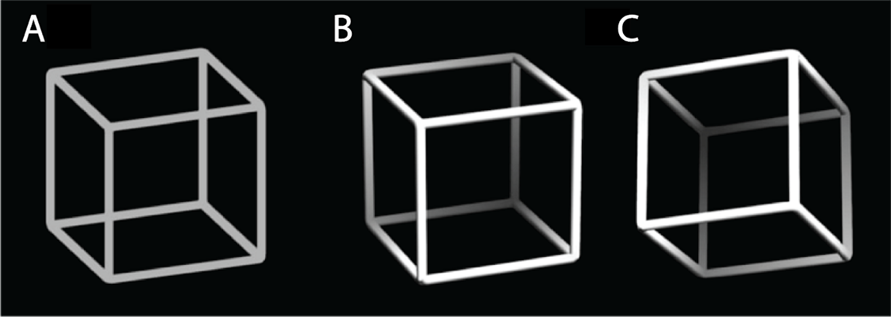

Often, the information we get from our senses is unclear or ambiguous, and can be interpreted in more than one way. A famous visual illusion illustrating this idea is the Necker Cube (Figure 1A). This cube can be seen in two different ways: the side facing up can appear to point either toward the bottom right (as visualized in Figure 1B) or toward the top left (as visualized in Figure 1C). The visual input that our brain receives from the original Necker Cube in figure 1A does not allow us to differentiate between these two possible interpretations. Looking only at the sensory input, both explanations are equally likely. Which interpretation you see depends a lot on your expectations (try it!). Similarly, the “brainstorm / green needle” audio fragment yields at least two different interpretations that are almost equally likely, based on sensory input alone. The instruction (or intention) to hear one interpretation over the other strongly influences what you actually experience.

Figure 1. (A) The Necker Cube, which can be perceived in two different ways. Either as facing towards the bottom right corner (B) or towards the top left corner (C).

Winner takes all

But if the sound is so ambiguous, how come the perception of either “brainstorm” or “green needle” is so crisp and clear? That’s because the brain naturally tries to clear up confusion; it looks for one clear way to understand the world, even when many other interpretations exist. Most theories of consciousness say this happens because any conscious experience involves widespread brain activity, simultaneously reaching many different brain regions, which allows only one experience at a time. So, the interpretation that wins (like “brainstorm”), albeit very slightly, self-reinforces, thereby temporarily suppressing other possible interpretations (like “green needle”). Through this winner-takes-all principle, a very clear experience of the word “brainstorm” surfaces in your conscious experience.

If you want to learn more about how your brain generates a conscious experience of the world around you, then read “Being you” by Anil Seth, or “A trick of the mind” by Daniel Yon!